While the coronavirus pandemic spread around the world, a destructive disease was also wreaking havoc underwater on coral reefs: stony coral tissue loss disease.

This fast-spreading disease, which can rapidly kill huge swaths of coral if left untreated, was recently discovered in coral reefs off the coasts of Roatán, Guanaja, and Utila, three Caribbean islands that are part of the Bay Islands National Marine Park in Honduras.

These were disheartening discoveries for the dedicated teams of people working to save coral reefs in the region, but unfortunately, they didn’t come as a surprise. Scientists confirmed the first sighting in Roatán in September 2020, then in Guanaja and Utila in the summer of 2021.

“I just felt profound sadness because this disease is rampant and it’s caused so much damage everywhere else,” says Jenny Myton, the Mesoamerican Regional Program Director for the Coral Reef Alliance (CORAL). “It was only a matter of time.”

Stony coral tissue loss disease, explained

Stony coral tissue loss disease is a relatively new disease that was first discovered on coral reefs off the coast of Florida in 2014. Since then, it has spread to over 18 countries, including México, Puerto Rico, Belize, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Dominican Republic, and the Bahamas.

Once it reaches a coral colony, the disease begins to kill the soft tissue of more than 30 different species, eventually exposing the coral’s white skeleton. Without treatment, the disease looks as if it’s turning the coral to stone.

“You can see it—it looks like the tissue of the coral is sloughing off,” says Myton.

The disease spreads rapidly and tends to be lethal, which is why scientists were so concerned when it reached Honduras. It can be spread by fish, who bite off a piece of infected coral elsewhere and then swim to a new region. Divers and boaters can also spread the disease if they don’t carefully wash their dive gear and their bilge pumps, Myton says.

Treating the disease

The disease didn’t come as a surprise—in fact, CORAL began connecting with partners in Cozumel and Roatán in 2019 to plan for its arrival. The disease had already been detected in Cozumel, and our partners in México were able to share their lessons learned and help our Roatán partners prepare.

As soon as the disease was detected in Honduran reefs, scientists and all the 14 organizations in the Bay Islands National Marine Park Technical Committee came together and immediately sprung into action. Organizations like Roatan Marine Park (RMP), Bay Islands Conservation Association (BICA), Administrative Commission of the Free Tourist Zone of the Bay Islands (ZOLITUR), Healthy Reef Initiative (HRI), and the Honduran government’s National Institute for Forest Conservation and Development teamed up to create a path to respond to the disease.

“Without the leadership of our local partners, facing this monumental task would not be possible,” says Pamela Ortega, CORAL’s Program Manager on Utila. “The co-managers, supporting organizations and volunteers are the superheroes, working tirelessly to monitor, treat, and educate people about the disease. Without their dedication, we would be facing a much grimmer picture.”

But the timing was tough—many of these organizations were simultaneously dealing with the effects of COVID-19. They were faced with two concurrent pandemics, one wreaking havoc underwater and another hurting their operations and revenue streams above water. CORAL prioritized helping these organizations find critical funding to stay afloat during tourism lockdowns, allowing them to focus their efforts on addressing the crisis unfolding underwater.

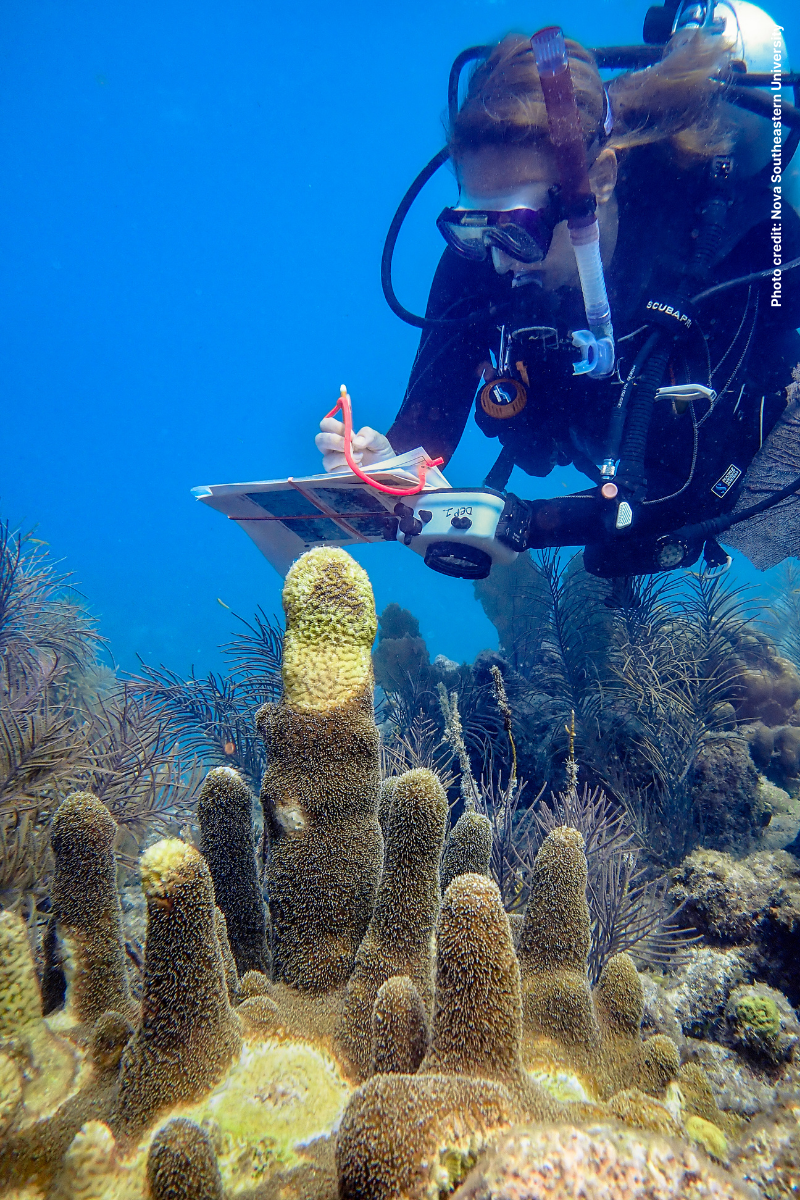

Working hand-in-hand, the local organizations began applying a special topical antibiotic around the diseased patches or lesions on the coral, which can help stop the spread of the disease. The antibiotic application process requires a lot of time and specialized manpower, and researchers must revisit the same colony over and over again to re-apply and track the disease’s progress.

This makes it essential for all the various stakeholders to work together and streamline their approach. To that end, researchers are also encouraging local divers in the area who want to help fight the disease to collaborate with the co-managing partners, who are coordinating the antibiotic application process from start to finish and have a comprehensive vision for treatment.

“This is like a triage center for corals,” Myton says. “You have to prioritize what you’re going to treat, and then you have to monitor it, and go back again and again. It works, but you have to be on top of it.”

CORAL is also helping local partners build a new rescue center that will help preserve corals that are resistant to the disease, Myton says.

In the future, scientists could undertake micro-fragmentation, a special re-growth technique that involves breaking coral into small pieces, to help restore the reefs affected by stony coral tissue loss and other diseases.

The new center, which is still in the planning stages, will be located in Sandy Bay, Roatán.

“In Roatán, RMP and BICA have been applying the antibiotic nonstop but we’re getting to the point where it’s not enough,” Myton says. “They are trying to identify the coral species that have not been as affected by the disease. They’re resistant in some way, so they’re focusing on trying to make sure that those corals can reproduce and survive.”

Moving forward

As work to launch the new rescue center and apply the antibiotic continues, local organizations and CORAL continue to address the ongoing threats to coral reefs in the area.

Though the antibiotic is effective at preventing the spread of the disease, it’s also vitally important that the coral colonies have healthy water around them as they recover.

“You need to ensure that you have the conditions for corals to recover,” Myton says. “You can compare this disease to COVID-19: if you have an underlying condition like diabetes and you get COVID-19, you’re more likely to succumb. If the reef has other underlying conditions like bad water quality, from sewage or other nutrients from runoff, then it’s more likely that the corals will succumb to disease—this one and others.”

CORAL will also continue to support Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment, or AGRRA, efforts to benchmark the health of coral reefs in the region every two years. Led by the HRI and supported by a number of organizations and volunteers, this assessment tracks various coral reef health indicators, such as fish populations, the benthic organisms who live on and inside reefs, and coral size and tissue mortality.

Comparing assessments over time helps scientists understand what’s working and what needs more attention in their bid to save the reefs.

“It gives us a path to move forward,” Myton says. “We can monitor how we’re doing and what we need to be working on. It helps us understand what’s happening biologically and where our management actions have to be focused in the future. And it can also tell us if we’re actually doing our job.”

Regularly monitoring the reefs also helps scientists react quickly and collaboratively to fast-acting threats and deadly diseases like stony coral tissue loss disease. In both the short and long term, the key to saving coral reefs is working together.

“It is important that as a community, we all take action as partners and try our best to be involved and support others, and hopefully we will experience both coral reef and community resiliency,” Ortega says.