It’s 6:45 a.m. when Paola Urrutia arrives at Tela Bay. She makes her way down to the water, finds the spot where the fishermen will disembark after their morning catch, and sits down to wait.

On the northern Caribbean coast of Honduras, Tela Bay sits at the bottom of a gently sloping tropical forest, marked by beautiful white sand beaches and sparkling turquoise water. It’s home to some of the healthiest coral reefs in all of Central America—scientists estimate that the bay averages about 70% live coral cover, the highest in the Mesoamerican Reef system.

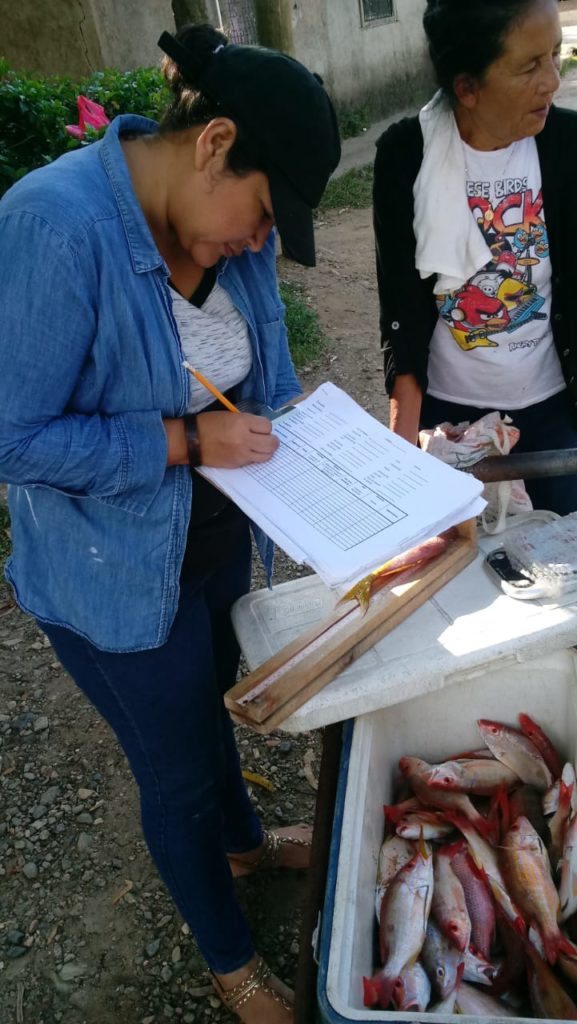

When she sees the first boat begin to approach, Urrutia pulls out her equipment and marks down the time of arrival. She approaches the vessel and requests permission to collect data from their catch. The fishermen are used to her presence by now and her research has become a standard part of their disembarkation routine. She analyzes the fish they caught, carefully documenting all of her measurements.

Urrutia was hired as CORAL’s first community scientist in Honduras in 2015. Today she’s one of three community scientists that CORAL employs in the country to gain a better understanding of what is happening to local fisheries.

CORAL’s community scientists live in or near the communities where they work, which helps them build relationships and gain trust. They tend to be women, most often from minority groups, who have struggled to find adequate employment and face social and economic vulnerability. Though several of them come from fishing backgrounds with relatives and family members who fish, this is their first foray into science and research.

CORAL Program Coordinators train them on the basic science of fisheries and how to appropriately and accurately collect and monitor data.

“I have changed a lot thanks to CORAL,” says Greissi Lizeth Villatoro, who began working as a community scientist in early 2019. She works in Laguna de los Micos, a popular fish nursery in the lagoon that feeds Tela Bay. “I have learned many things that I did not know, and taking the data has also helped me a lot.”

The program not only provides the scientists with paid employment and much-needed economic stability, but CORAL’s Program Coordinators also encourage the women to work toward personal goals and pursue their education as a way of investing in themselves and their families.

Urrutia herself left her role as a community scientist in 2016 to go back to school at the urging of CORAL’s then Program Coordinator. Now that she has graduated, she has come back to CORAL, and has taken on more duties. She’s now supervising the maintenance and data collection of CORAL’s experimental aquaculture project in Tela—a project designed to create an economic alternative for fishermen—in addition to working as a community scientist in Tela Bay.

Through their relationships, the women have created a network of fishermen that help support science and understand the importance of rules and regulations. They’ve become a regular presence at community meetings, and report back on their findings to help fishermen understand what is happening underwater.

“The most important impact that I’ve noticed is that now people have more respect for closed seasons,” says Urrutia. “Before, 100% of fishermen went out to fish during the closed season, now only between 10-20% are going to fish illegally.”

Urrutia has also noticed an increase in fishermen who talk openly about complying with regulations—they chat with each other about following regulations and avoiding damaging practices like anchoring on the reef. Practices that protect the environment are becoming more commonplace.

Villatoro has also seen changes among the crabbing community in the lagoon near Tela. “Through the data collection, the crabbers have been learning the appropriate size of crabs to capture,” says Villatoro. “The fishermen’s company has stopped buying small crabs, and several fishermen have stopped using illegal nets where the mesh size is less than three inches.”

This change in behavior is a direct result of the relationships and trust the community scientists have built within their communities. They have gained a reputation as being allies, and fishermen see them as a key component to decision making and managing their resource.

“In the community where I come from, the work of a community scientist is seen as a means to improve fishing and to find out how the resource is doing,” says Ana Bessy Valdez. She joined the CORAL team in July 2019 and was the first community scientist to start monitoring in Trujillo Bay, the southern border of the Mesoamerican Reef system. “Fishermen are aware that data collection is to improve fishing and they want to know what alternatives they have for bad seasons.”

Though not all of the fishermen that Valdez meets choose to provide her with data, the majority enjoy collaborating.

Back in Tela, Urrutia casually chats with the fishermen while she takes her measurements. She asks them about their fishing location, depth, travel time, and expenses. The fishermen know Urrutia by now, and they trust her. They tell her who is still out on the water, and when and where they will likely land. She packs up her equipment, and relocates down the beach so she can be ready for the next arrival.

When the last boat arrives at 10:00 a.m., she takes her last measurements, and bids her fishing friends farewell. She’ll be back tomorrow, same time, same place.