It’s 5:30 a.m. on a Wednesday, and Erica Perez leaves her house in Hilo to start the slow, dark, one-and-a-half hour drive to the South Kohala coast on the other side of Hawai‘i’s Big Island.

She arrives at the first site at 7:00 a.m., where she meets long-time community volunteer Keith Neal. They put their masks on, unload the testing equipment and Perez wades her way to knee-deep water to collect their first water quality sample. Neal stays behind to watch the equipment. It’s the first of five sites they will collect samples from that morning, trying to hit all before the sun has a chance to break down bacteria.

Once sampling is finished around noon, they part ways and Perez travels south to drop the samples off at two different laboratories before making her way back home to wait for the results.

The sampling is part of an island-wide collaborative effort that Perez launched as CORAL’s Program Manager on Hawai‘i Island. The project, called Hawai‘i Wai Ola, brings together eleven different organizations, volunteer community members, and scientists to champion water quality issues on Hawai‘i Island.

Right now, the Hawai‘i Department of Health samples and reports on water quality at sites around the island. But their resources are scarce, so sampling is limited and inconsistent.

“Our capacity on-island has been hit hard the last five years between hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and now COVID,” explains Perez. “If we want to continue to be informed and have vital information about our water resources while our government is so strained, then we need to support our government in as many ways as we can.”

The plan was to launch a volunteer team this summer that would regularly collect water quality samples in Kona, Hilo and South Kohala. Their efforts would bring a more robust and consistent understanding of water quality issues across Hawai‘i Island and reduce some of the pressure on the Hawai‘i Department of Health.

But when COVID-19 hit, the volunteer program was put on hold and in-person training was canceled. As case numbers continued to rise on the island, it became near impossible to allow groups of volunteers to gather in a safe manner to sample, let alone to be trained. And beaches were closed, so team members couldn’t access sampling sites.

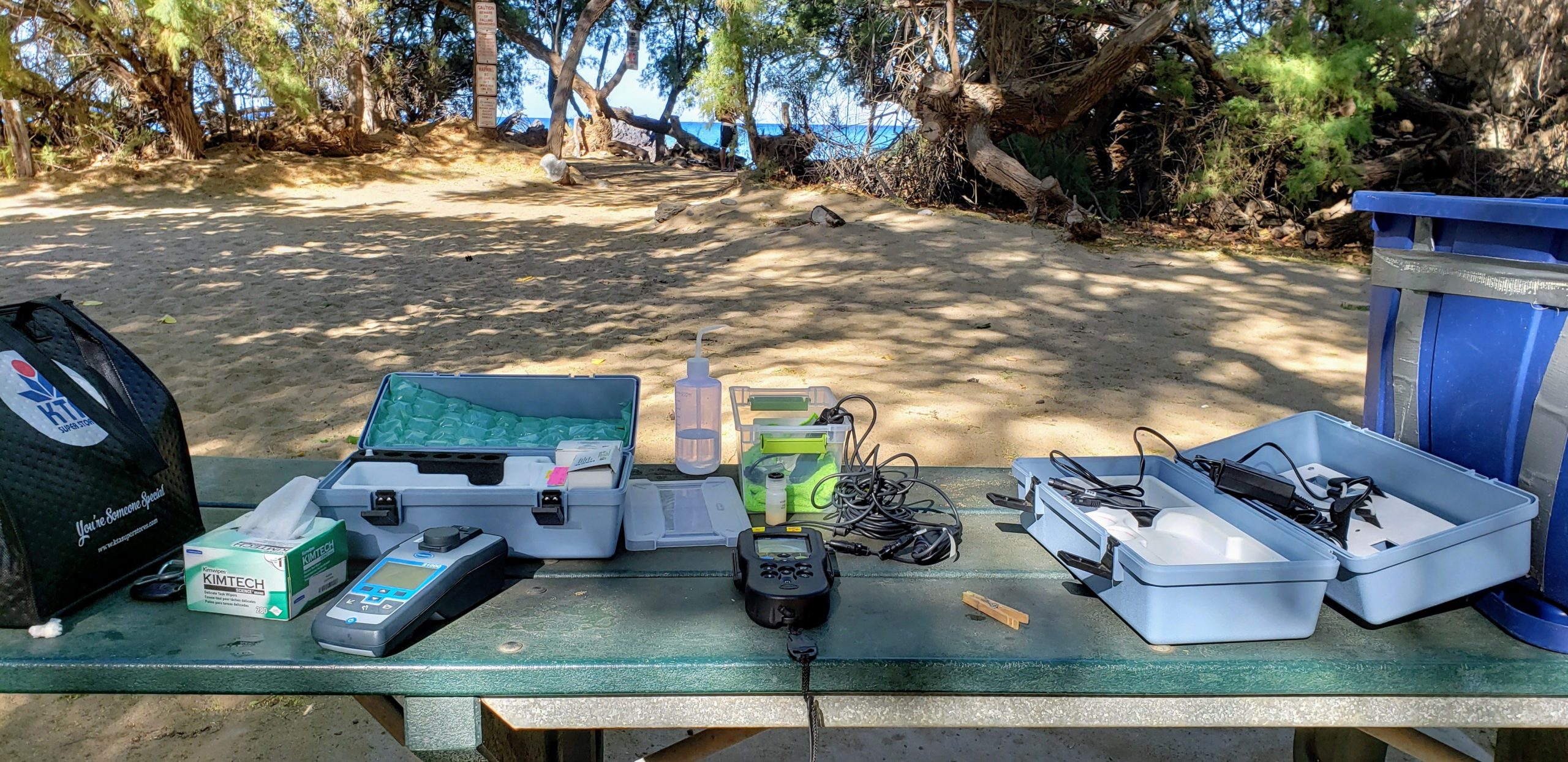

Typically, a sampling team consists of three people. “The sites are really spread out and there is a lot of equipment,” describes Perez. “It’s hard to load and unload on your own, and you can’t just leave thousands of dollars of equipment on a table while you run into the water to collect a sample.” However, Erica and other Hawai‘i Wai Ola members have been forced to occasionally go out on their own, taking advantage of regulatory exemptions to access beaches when possible.

That’s because this is a prime time for sampling. There’s a silver-lining to the fact that tourism was restricted in the islands and most beach activities were forbidden: the team had an opportunity to understand what water quality looks like when no one is visiting the beaches.

“I can’t stress enough the importance of collecting data when people weren’t using the resources.” says Perez. “There were no tourists. Only a few locals were on the beach, very few people were using sunscreen and getting in the water. It was the perfect opportunity to create a baseline for what minimum-use looks like. Then, when things fully reopen, we can look at that baseline again with more people and more use and compare the two.”

Perez is excited for the opportunity to gain a better understanding of how much human use and tourism affects water quality—even if it means continuing to collect samples herself with just one other person to help. It’s an opportunity they wouldn’t have had if 2020 hadn’t brought so many challenges. In the meantime, though, she’s working hard to convert the volunteer training into an online platform so volunteers will be ready and prepared to start sampling when it’s safe.