By: Ben Charo, Conservation Science Program Coordinator

If we don’t curb greenhouse gas emissions and slow the warming of our oceans, 99% of the world’s coral reefs are predicted to be gone by the end of this century. Indeed, reefs are already in serious decline. So it might surprise you to hear that within the next few hundred years, corals could adapt, rebound, and survive if given the chance to evolve. The key? Genetic variation.

Genetic variation is the fuel of evolution. It’s also a big part of what makes every individual organism on this planet unique. Even the slightest genetic differences can lead to discrepancies in height, eye color, the probability of contracting diseases, and other distinctions. Organisms with genes that are best adapted to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce, sending their unique genetic code on to the next generation. This process is known as natural selection. Over multiple generations of natural selection, species can begin to display new traits and characteristics—you’ve likely heard this referred to as evolution.

It stands to reason that the more genetically diverse a population of organisms is, the more diverse its pool of individuals will be, and the more likely that some of those individuals will be able to adapt to whatever circumstances arise. It’s this idea that is essential to coral reefs surviving the heat stress created by climate change.

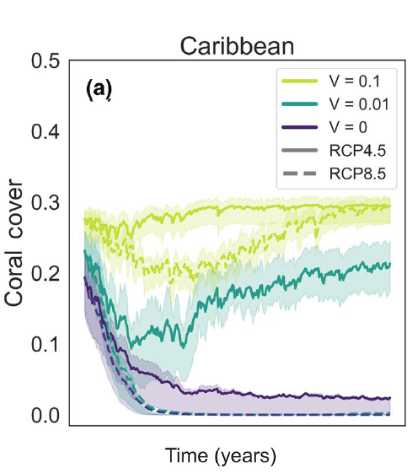

In an article published in Global Change Biology last year, CORAL team members and partners confirmed that genetically diverse coral reef networks were much more likely to survive warming waters than their less diverse counterparts. The graph (Figure 1a from the paper) illustrates a number of simulations run for the Caribbean region. In the graph, RCP8.5 represents a high-greenhouse gas emissions scenario (leading to a warmer planet and warmer oceans), while in RCP4.5, emissions are stabilized. You’ll notice that corals without genetic variability (V = 0) were wiped out completely with high emissions and barely survived with low emissions. Corals with moderate variability (V = .01) were able to recover in a cooler climate scenario, but perished under the high-emissions scenario. And corals with high variability (V = 0.1) survived regardless of climate circumstances.

When these simulations were run on coral reefs in other regions across the globe, corals behaved very similarly. The key takeaways: 1) genetic variability is critical to coral reef survival, and 2) we must meet corals halfway by acting urgently to reduce emissions.

Our research also found that genetic connections between coral reefs were crucial to their prospects. When corals reproduce, their larvae move with ocean currents and can be carried along to other reefs, where they settle and grow. That means coral reefs are genetically connected to one another through flows of larvae from reef to reef. According to our research, coral reefs that received larger amounts of larvae from other reefs were more likely to survive the effects of climate change than those that received fewer. This was especially true for reefs in colder water that received heat-adapted larvae from hotter reefs. In short, preserving genetic variability is important, but so is promoting genetic exchange, especially from reefs that are already adapted to high temperatures.

These findings present us with a few key implications for how we can help corals survive warming oceans. First, we must reduce carbon emissions and slow the rate of climate change to give corals a fighting chance. National governments in countries that are most responsible for global carbon emissions must bear the brunt of this work, but individuals can make a difference as well. Second, we must protect a diversity of reefs that are themselves genetically diverse. Doing so increases the odds that heat-adapted individuals will be present and naturally selected. Third, we can’t just protect individual patches of reef; we must ensure that reefs are protected in connected networks to allow the exchange of genes. And finally, we must pay particular attention to the presence of hot reefs in these networks, which should allow heat-adapted larvae to spread to other reefs.

There’s one last piece of the puzzle to coral reef survival: reducing additional pressure from local stressors. When confronted with threats, such as wastewater pollution or overfishing, reefs are less likely to recover from coral bleaching events. We must make sure corals aren’t hit from multiple angles at once by tackling these issues.

Through global conservation science and locally-based efforts, CORAL is leading the charge on making this vision for coral reef survival a reality. In Hawai’i and the Mesoamerican Reef region, our conservation teams are improving water quality, protecting reefs from overfishing, and eliminating as much additional pressure on these ecosystems as possible so they’re able to withstand the threat of climate change.

Meanwhile, our Global Conservation Science team is turning this science into action by influencing and leveraging partners, fieldwork, and technology to drive adaptation-focused conservation solutions that will rescue coral reefs from the effects of climate change. Our approach consists of three main pillars:

- Supporting conservation practitioners by developing tools they can use to identify and protect reef networks capable of adaptation.

- Influencing the conversation about coral reef conservation and conducting outreach efforts to make adaptation an important part of the dialogue on coral reef protection.

- Teaming up with partners and allies, such as the Ocean Sewage Alliance and the Improving Coastal Health team of the Science for Nature and People Partnership (SNAPP), to magnify impact.

If you’re a coral reef conservation practitioner, we hope you’ll consider the principles described above as you approach reef protection. And, no matter who you are, we hope you’ll use your voice to advocate for climate-smart policies, and invest in CORAL’s groundbreaking work to save coral reefs. We invite you to explore our website, coral.org, to learn more about what we do and about our approach to conservation.