Atlases and maps are helpful for planning trips and exploring geography, but researchers believe they may also serve another, more important purpose: Identifying priority coral reef conservation areas.

With a new three-year $300,000 grant from Lyda Hill Philanthropies, the Coral Reef Alliance (CORAL) and partners can begin to test their hypothesis that satellite-based imagery and high-tech maps of the world’s coral reefs can help inform conservation decision-making processes and actions.

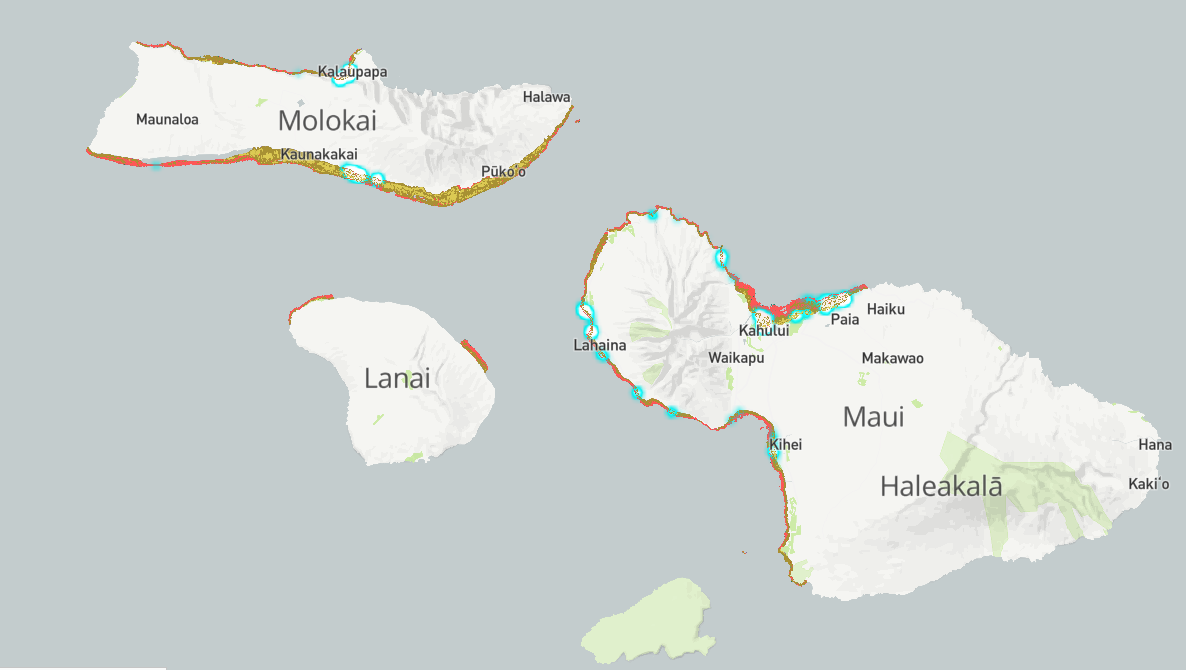

More specifically, researchers will use maps to remotely investigate and identify coral reefs that are in locations with high levels of habitat and thermal diversity, characteristics that help the corals adapt to rising ocean temperatures and other impacts of global climate change. Conservation can then be targeted to those key locations where the focus is on reducing local stressors to keep corals as healthy and resilient as possible.

Dr. Helen Fox, CORAL’s conservation science director, is spearheading the initiative, working alongside Allen Coral Atlas partners, researchers at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, and other colleagues.

Before joining CORAL in April 2020, Fox led field engagement for Allen Coral Atlas, a pioneering global map of coral reefs created with high-resolution satellite imagery and other tools. This collaborative effort involves Arizona State University’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, the National Geographic Society, Planet, the University of Queensland, and Vulcan Inc., which launched the project in 2018 with support from Paul G. Allen; sadly both Allen and another of the project’s founders, Dr. Ruth Gates, passed away in October 2018.

The Atlas Field Engagement Team also received support from Lyda Hill Philanthropies, a charitable organization created by Dallas-based entrepreneur Lyda Hill, who supports advancements in science, nature, community, and nonprofit empowerment.

“The Atlas is now emerging as a tool for mapping corals globally,” says Fox, who has decades of experience in coral reef ecology and remains an advisor for Atlas Field Engagement Team at the National Geographic Society. “Our question is: Can the Atlas help us detect characteristics of a reef that would be indicative of habitat diversity, and potentially also thermal diversity, which would help drive evolutionary rescue? Basically, can we get a proxy for this diversity and might that also serve as a proxy for adaptive capacity or resilience?”

The connection between diversity and adaptation

This new research builds on CORAL’s core theory of change: That coral reefs can adapt to the effects of climate change under the right conditions.

To help coral reefs adapt, CORAL has focused its efforts on actions that reduce local stressors on reefs, such as improving water quality and ensuring sustainable levels of fishing.

Research shows that reducing local stressors over a connected and diverse array of reef types is critical for corals to be able to adapt to rising temperatures. And habitat diversity is linked with genetic diversity, which means that corals living in highly variable conditions may be more likely to adapt to rising ocean temperatures.

Protecting a large, diverse network of reefs will give corals the best long-term chance of survival. To that end, CORAL has set a goal of creating 45 networks of healthy corals that can adapt to climate change—by 2045.

“We need to protect reefs that live in hot water, reefs that live in cooler waters and reefs in the middle because that diversity is the fuel that makes the evolutionary engine run,” said Dr. Madhavi Colton, CORAL’s Executive Director.

Now, researchers want to understand: Can maps and other data be used to detect those areas with greater habitat diversity, basically serving as a proxy for adaptive capacity? Answering this question is the project partially funded by the Lyda Hill Philanthropies grant.

Studying reefs with satellite imagery

This grant will also help support Anna Bakker, a doctoral student at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science who is studying characteristics of reef resilience. Bakker is advised by Sam Purkis, Professor and Chair of the Rosenstiel School’s Department of Marine Geosciences; Purkis also serves as chief scientist of the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, a nonprofit that has undertaken many coral reef surveys and high-resolution habitat mapping expeditions.

One question researchers hope to explore is the level of detail about reef habitat that satellite imagery can capture. If the Atlas can detect high levels of habitat diversity, that could potentially mean high levels of thermal and genetic diversity—the key to building a reef’s adaptive capacity.

The ability to remotely assess habitat diversity from satellite imagery could have important implications for on-the-ground reef protection and conservation. The potential new adaptive capacity proxy could help inform marine spatial planning processes, the main way that countries around the world decide which areas of the ocean to protect.

“The Atlas itself can serve as a better base layer to feed into that planning process and then if we’re able to develop this adaptive capacity proxy, that could also get used as a layer in this marine planning process,” Fox said. “If you have two areas you’re considering for marine protected areas and they are equivalent in all other factors, then if one area has more adaptive capacity, you would choose that one.”

Time is running out

This work—and all of the work CORAL undertakes with its partners in the conservation community—is vitally important for ensuring that coral reefs survive the effects of climate change, now and into the future.

Coral reefs are dying off at alarming rates, with some 27 percent lost in recent decades and 75 percent of remaining corals under threat from local impacts and global climate change. Without immediate action, coral reefs may disappear from the world entirely; their fate will likely be determined within the next 25 years.

The loss of the world’s coral reefs would not only represent a biodiversity crisis, but it would also cause a humanitarian crisis, as an estimated 500 million people depend on the reef ecosystem for income and food.

“We have a rapidly diminishing window to help reefs and create the conditions that will allow reefs to survive as temperatures continue to rise on our planet,” said Colton. “The Lyda Hill Philanthropies’ funding is supporting our ability to turn our cutting-edge scientific research on evolutionary adaptation into action around the world.”