My father and I share a love of the ocean and diving. These days, we live 3,000 miles apart, he’s on the East Coast and I’m on the West. But we take the time to visit our respective hometowns and occasionally, to dive together where tropical corals grow.

For me, dive travel is a much-needed escape from the challenges and speed of everyday life. It is also an opportunity to visit the array of coral species that I dedicated four years of my life to learning about during graduate school. In early November, my father and I visited one of my favorite Caribbean dive spots, Little Cayman Island and the awe-inspiring mosaic of the Bloody Bay Marine Park.

As I stepped off the boat with a giant stride on our first dive, I saw a sudden explosion of color and movement on the reef below. Mixed feeding groups of parrotfish flowed over the reef in a seemingly coordinated ballet of interweaving movement. The crunch of their beak-like fused teeth biting into coral was audible at 20 feet.

I noticed clouds of tiny nearly transparent mysid shrimp schooling for safety just above coral heads. A diversity of coral, fish, sponges and other invertebrate species, even a tiny seahorse, caught my eye as we explored the reef and sand patches that surround and protect the island.

What struck me most, besides the wicked humor of my Massachusetts dive buddies, was that the walls and shallows of Bloody Bay Marine park felt like a healthy reef, from the 15’ shallows to the nearly vertical wall that descends 3,000 feet into the deep blue.

The colors were brilliant and diverse. We saw the sun-yellow and depthless-black stripes of a juvenile French Angelfish. Numerous and stately barrel sponges stood sentinel on the wall edge, having looked out at the same view for the past 400 or more years. In the shallows, a barely discernible surge caused lacy purple sea fans to sway and soft corals to tremble like many-fingered jazz hands.

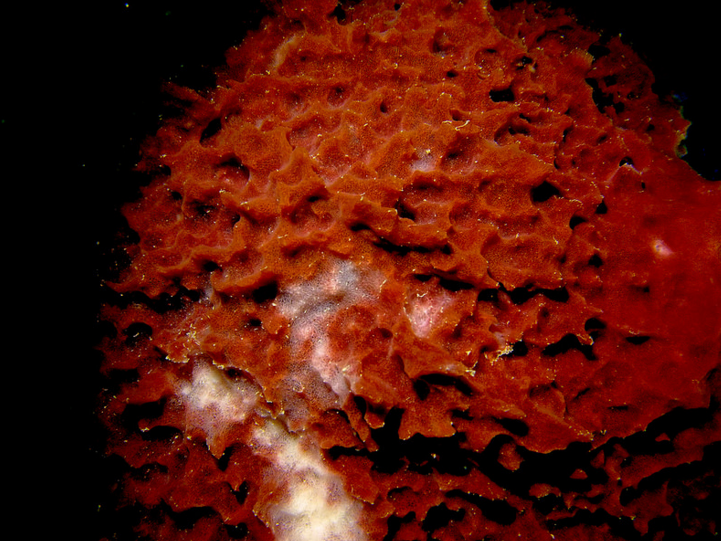

On every dive the vibrancy of the life under the surface surprised, awed and inspired hope. The reef and near vertical walls of Little Cayman are special to many divers, photographers and scientists from around the world. But, of course, today’s reefs are not the same as they once were. Around both Grand and Little Cayman islands, I saw corals with patches of pure white–a sign of recent bleaching. A few others were losing the battle with aggressive overgrowing or boring sponges.

Corals around the world are under stress. In some places, they have already been pushed beyond the threshold of recovery due to climate change and other human activities.

Climate change is the big one that we cannot wait any longer to address. Right now, the world’s political leaders are gathered at the U.N. Climate Summit (COP21) in Paris and are discussing how to save the world from catastrophic climate change.

Even carbon credits are an insufficient price tag for the value of nature and healthy reefs. The risk of what we will lose on reefs and in communities around the world is too big to stick to the talking points or leave to the elected leaders of our planet to fix.

This is why I have joined the CORAL family, to be a voice for coral reefs and the communities that depend on them, to help fight for the health, diversity and sustainable future of corals, humans and our planet as a whole.