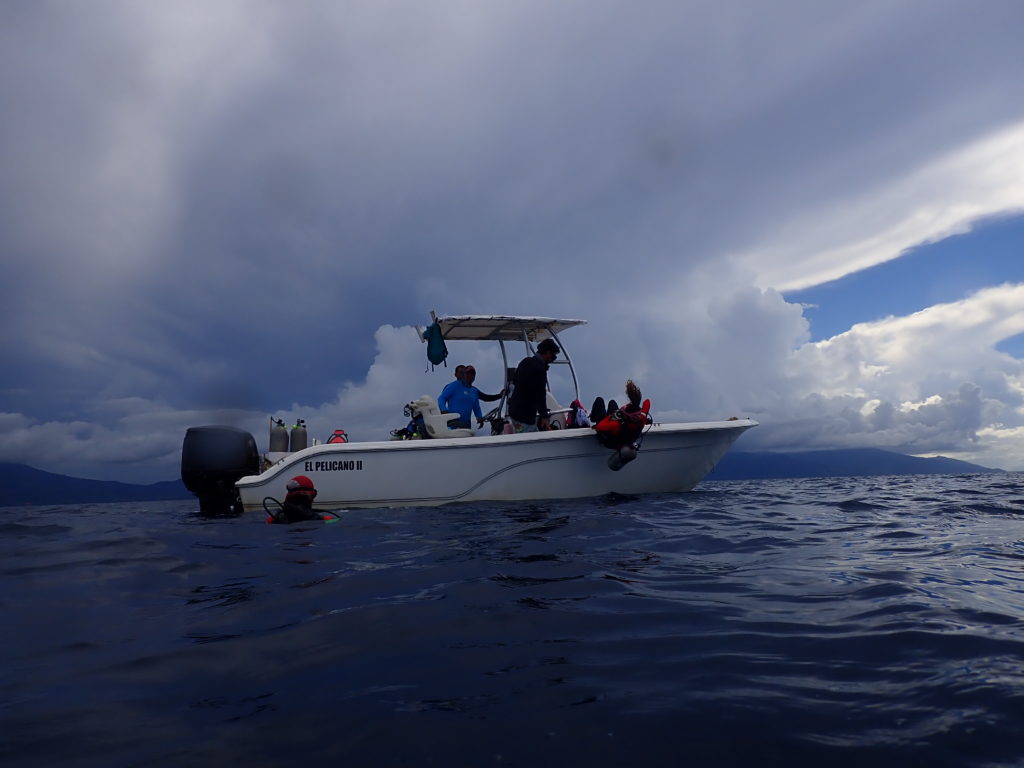

Local scientists from CORAL and the Healthy Reefs Initiative (HRI) made an exciting, new discovery during this year’s coral reef monitoring in Trujillo, Honduras. With the help of nearby fishers, they found multiple sites of new coral reefs that have not previously been monitored or studied by the local scientific community.

For a while, local scientists suspected there were new reefs, but were unable to find them due to bad weather and other complications. “This is great news and we’re hoping it is just the tip of the iceberg,” says CORAL Conservation Program Director Jenny Myton. “It’s possible that there are even more reefs nearby.”

Trujillo’s newfound reefs are functional and have an estimated 12 to 16 percent live coral cover, compared to Trujillo’s average cover of just nine percent. If properly protected, new reefs in Trujillo may be beneficial for the entire Mesoamerican reef region.

Establishing Networks of Healthy Coral Reefs in Mesoamerica

According to HRI scientist Ian Drysdale, Trujillo’s new reefs are considered a “sister” to the reefs in Tela Bay, which are more than 100 kilometers away. This is because the dominant type of coral on the reefs is the same, as are many of the surrounding fish and wildlife. Studies show that fish connectivity between the two regions is high, with some scientists hypothesizing that Trujillo actually is a source of fish larvae for all of Honduras.

In fact, there is connectivity between coral reefs in many parts of Mesoamerica due to ocean currents. While spawning, reef-building corals release male and female reproductive cells known as gametes, which join together to form baby coral. The offspring then ride the current for up to three weeks before eventually attaching to a hard surface to grow.

“Marine currents can be very strong,” says Drysdale. “When massive spawning events happen [in Mesoamerica], it is in the rainy season with high winds, storms, and currents. This can send offspring farther away, versus when we have flat, calm seas.”

By discovering, monitoring, and protecting new reefs, like the ones found in Trujillo, we will also protect corals found in other parts of the ocean. With this knowledge in mind, CORAL works to establish healthy coral reef networks throughout Mesoamerica, thus protecting vital coral species, coastal communities, and surrounding wildlife.

Addressing Direct Threats Facing Trujillo’s Reefs

When examining the Trujillo reefs, both Drysdale and CORAL Program Coordinator Paolo Guardiola noticed a lack of fish and physical evidence of reef damage, which point to signs of overfishing.

“We saw anchor scars,” says Drysdale, discussing the devastating damage found on an entire row of barrel sponges amongst the reef. “An anchor went right across [the sponges] and the scar was more than a meter wide and 15 meters long.”

When protecting a network of sister reefs, it is important to address the direct threats facing each area. By minimizing overfishing and irresponsible practices in Trujillo, we will also improve the health of reefs in other locations.

That’s why CORAL turns directly to the local community in Honduras, working side by side with community scientists and local fishers to secure healthy fish populations for different reefs in the region.

“For about two and a half years, we’ve been collecting data to build a fisheries management plan,” says Guardiola. “If we protect reefs in Trujillo, we’ll also improve the local economy. Fishers will be able to collect larger fish and at higher quantities.” This ongoing data is shared with key stakeholders, like NGOS, local governments, and fishing communities, in order to create awareness and promote sustainable fishing practices that protect coral reefs.

As we continue to learn about Trujillo’s new coral reefs and the threats they face, our team, local scientists, and members of the community can continue to evolve practices and push for new protection measures—so coral reefs in Mesoamerica can continue to thrive for generations to come.

Learn how you can contribute at coral.org/donate.