There’s a certain romanticized notion of what it must be like to be a coral reef scientist: living in a tropical environment with beautiful white sand beaches, snorkeling and diving every day, surrounded by colorful wildlife and pristine turquoise waters. Sounds dreamy, doesn’t it?

And for Dr. Antonella Rivera, Principal Investigator for the Coral Reef Alliance (CORAL) in Honduras, part of that is true. She does get to visit beautiful tropical environments throughout Honduras. And she occasionally gets to snorkel and dive.

But the majority of her days are spent studying something that is entirely NOT romantic: sewage.

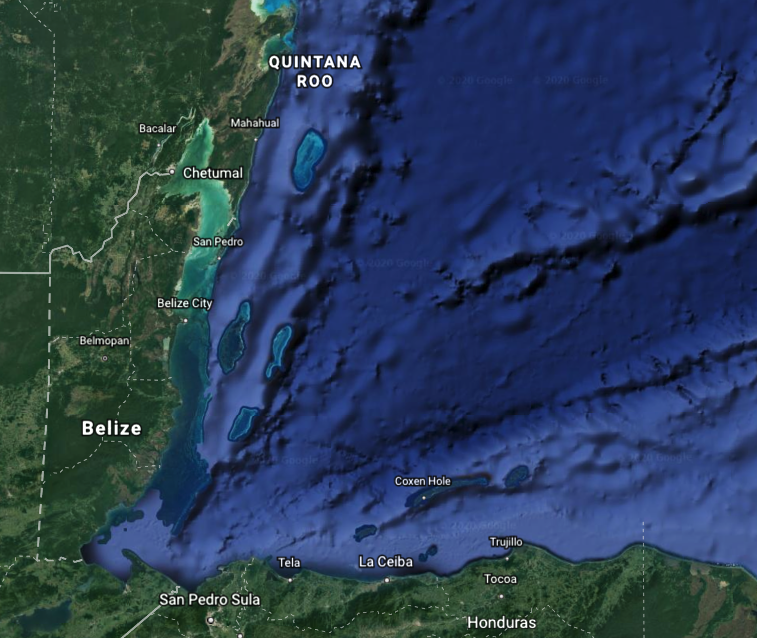

Dr. Rivera’s work focuses on the world’s second largest coral reef ecosystem—the Mesoamerican Reef. The Mesoamerican Reef stretches about 700 miles along the coasts of México, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras and supports millions of people with food, income and coastal protection.

In a typical year, it attracts nearly 16 million tourists to the region, bringing much needed revenue—though that came to a standstill in March 2020 when the global pandemic hit.

Despite these obvious benefits, the Mesoamerican Reef is currently listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List—largely due to coastal pollution. Lack of proper and efficient wastewater management in the region often means sewage enters the ocean untreated.

As you can imagine, sewage in the ocean poses a serious public health threat, putting a significant strain on the tourism industry. In some cases, tourists have sued hotels, claiming the contaminated waters and beaches made them sick. But the sewage also poses a serious threat to coral reefs.

“It’s heartbreaking that every year we’re seeing more and more algae on the reef,” says Dr. Rivera. “It’s obvious that sewage pollution is a big problem in the region, but we just haven’t had the data on a regional scale to prove that.”

When sewage enters the ocean, it brings nutrients that spur the growth of algae. The algae interfere with coral growth and compete with corals for space, and when that is combined with overfishing and the loss of herbivores who feed on the algae, the algae can quickly overcome the outnumbered corals. The sewage also contributes to coral disease, further stressing the reef.

There are few efforts in the region to monitor water quality and better understand the cause and effects of sewage pollution. At CORAL, we have a robust water quality monitoring program on the island of Roatán in Honduras that started seven years ago. But at a regional level, data collection is patchy and site-specific, and there’s no platform or organized effort to tell the full story of what’s really happening on the Mesoamerican Reef as a whole.

Until now.

When tourism came to a standstill in early 2020, Dr. Rivera and the rest of the CORAL team saw it as an opportunity. The low levels of tourism provided the perfect chance to understand the effects that visitors have on the inadequate or non-existent wastewater treatment systems in the region.

We quickly partnered with the Healthy Reefs Initiative, Summit Foundation, and local partners to launch a regional water quality monitoring program and build upon some of the more local efforts that are already happening.

The first phase of the program will explore the effects of tourism on water quality. The team will begin collecting monthly water quality samples in the next few weeks at three major tourism-impacted locations in each country, using parameters that will help quantify the impacts of tourism. As tourists begin to return to the region, the team expects to see a drastic change in water quality.

The second phase will explore the effects of other pollution contributors, like agriculture, and will use these data to begin advocating for policy changes.

Though Dr. Rivera never anticipated this kind of potty talk would consume her days as a coral reef scientist, she couldn’t be more excited to be diving in.

“I’m excited about this new water quality work because it’s a way for us to scale up all the good work we are doing in Roatán,” says Dr. Rivera. “It makes me very optimistic that water quality, and its impact on coastal ecosystems, will finally be on the forefront of research and conservation in the region. We’ll be able to make a considerable impact on reef health.”