Coral bleaching events make headlines every year. And each year, bleaching events have become more frequent and severe. Take Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, for example: In the last five years, the reef has been hit by three record-breaking coral bleaching events—one in 2016, one in 2017 and another in 2020.

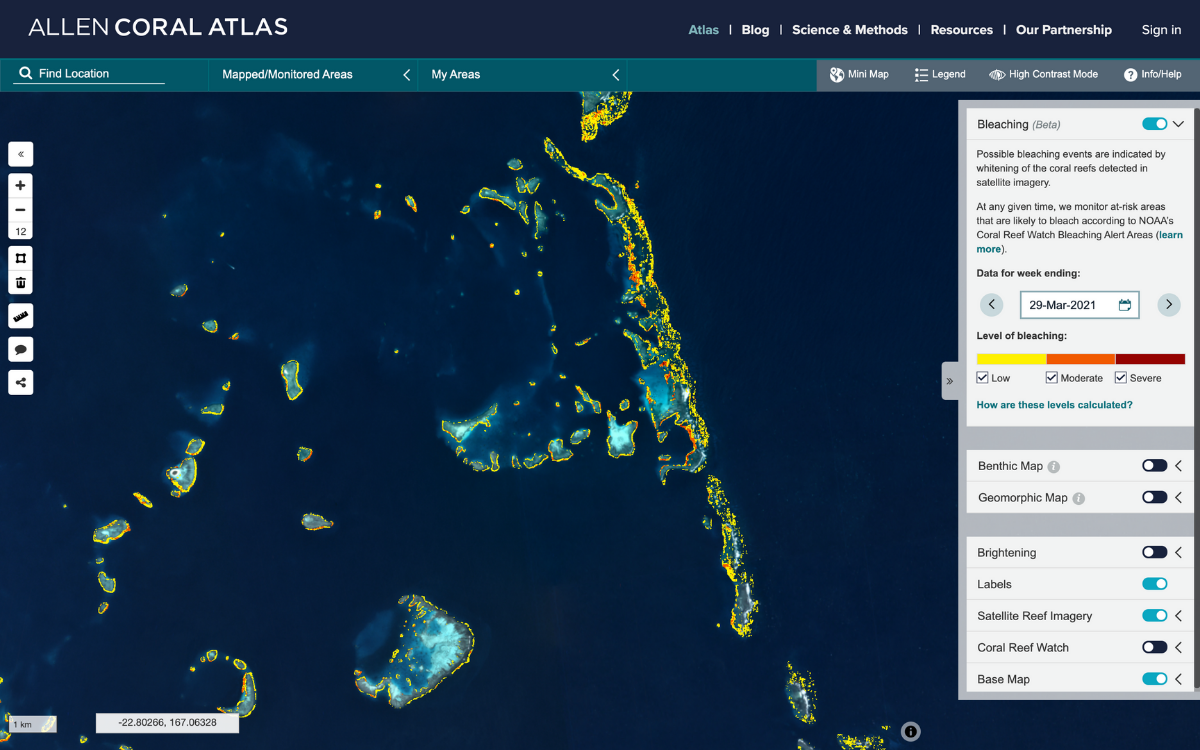

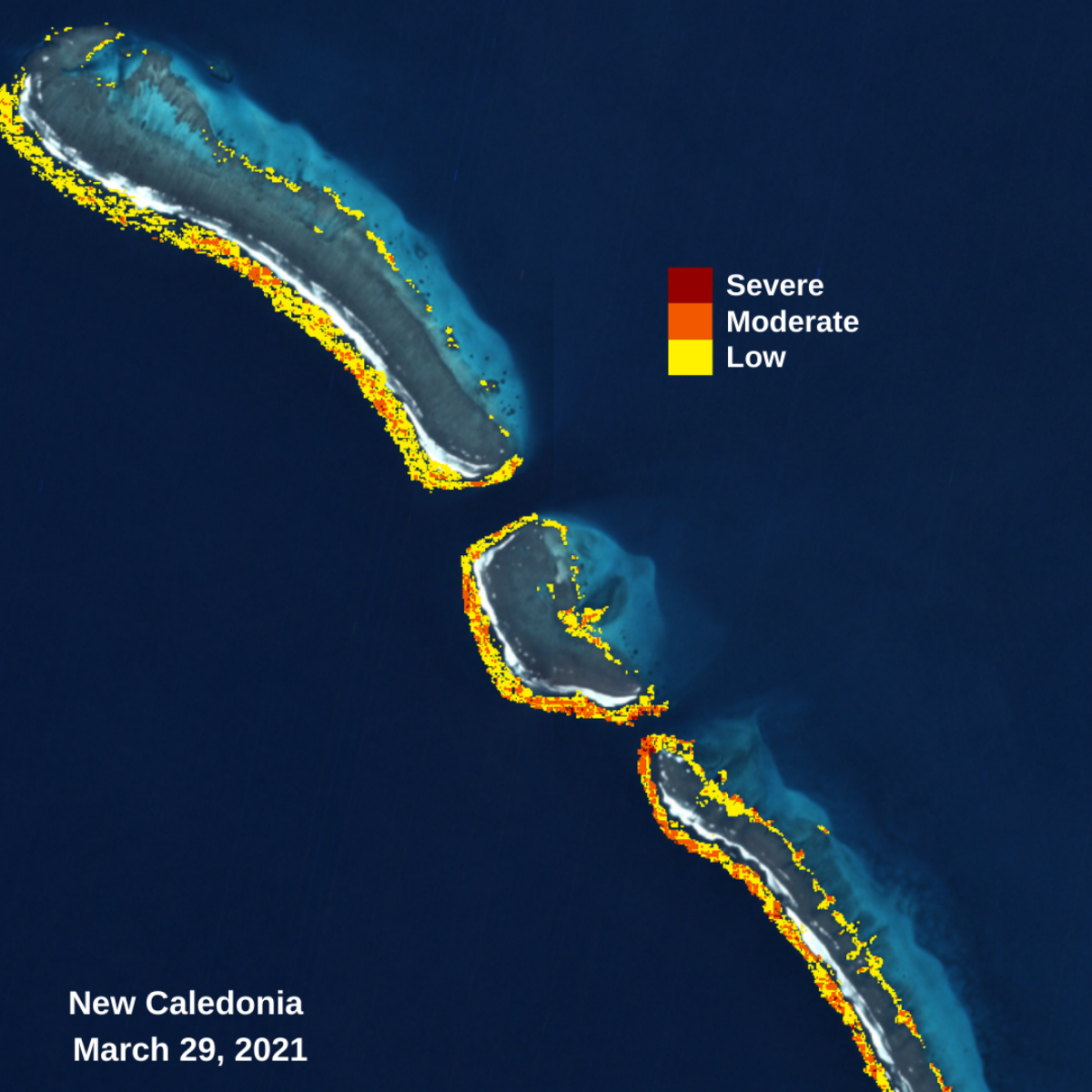

But the Allen Coral Atlas partnership (Atlas), a pioneering effort that uses high-resolution satellite imagery and advanced analytics to map and monitor the world’s coral reefs in unprecedented detail, just launched a new tool that will help conservationists stay abreast of these coral bleaching events—allowing them to take quicker action to help reefs recover.

The Atlas uses satellite imagery to detect coral bleaching events from space and then adds them to the free, open-sourced digital map. And to help make the system more robust and accurate, and ultimately become an indispensable coral bleaching monitoring tool for reef conservationists, they need a team to help ground-truth the information that’s being detected in space.

Enter Andrea Rivera-Sosa. As the Coral Reef Alliance’s (CORAL) new Project and Outreach Manager, Rivera-Sosa is tasked with uniting a global network of scientists who can get into the water to confirm what those satellites are detecting, and building consensus around a common mechanism for them to report their findings.

“Andrea is absolutely the right person for this job,” says Dr. Helen Fox, CORAL’s Conservation Science Director. “She did something very similar in the Mesoamerican Reef region, so she has a lot of experience thinking about bleaching, methodologies, and multiple stakeholders, and is a terrific science communicator—she’s the perfect fit.”

This new position comes as part of a three-year $850,000 grant from the Paul M. Angell Family Foundation. By joining Atlas partners like Vulcan Inc., Arizona State University, National Geographic Society, the University of Queensland, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the Nature Conservancy’s Reef Resilience Network, CORAL will help link the Atlas’s satellite products with networks of on-the-ground conservation scientists to provide new field information that will validate and develop the Atlas toolkit—beginning with coral bleaching.

“My first task is to study the various methods that stakeholders are using to document bleaching globally—and there are many—to assess the pros and cons of each and propose a unified metric that we can all follow without changing the way monitoring programs operate,” says Rivera-Sosa. “I’ll also track the places that are experiencing coral bleaching, but we have to start by building relationships with the people on the ground. Because coral bleaching is a global problem, I think we need to tackle it from a global perspective. And, as scientists, we have a real opportunity to come together right now.”

When ocean temperatures warm as a result of climate change, corals can become stressed and expel the tiny little algae that live inside of them, called zooxanthellae. The zooxanthellae use the sun to photosynthesize and provide corals with up to 90 percent of their food. Without their zooxanthellae, corals lose that important food source and can become very sick. And if they go too long in a bleached state, they can die. They also become more vulnerable to diseases and have a harder time overcoming other stressors, like poor water quality.

Rivera-Sosa’s position is an important piece of a larger effort to help the Atlas empower conservationists and scientists with the information they need to address these threats. Having a tool like the Atlas to aid in early bleaching detection will allow conservationists to respond in real-time and raise awareness to try to reduce other local stressors that will aid in the reef’s recovery. And as other threat detection systems are added into the Atlas, like heavy wastewater runoff, it will provide a better understanding of how all of these reef threats are intertwined. Ultimately, the Atlas will be an invaluable asset for scientists to communicate about and demonstrate the effects of climate change on coral reefs, and push for better policies.

Having this information will also aid in our research to better understand how corals adapt to climate change, and will inform our conservation activities intended to create the conditions that allow corals to evolve naturally. It’s a big job, and one that has high stakes for coral reefs and the people who depend upon them. But Rivera-Sosa isn’t fazed by the pressure. Instead, all she sees is opportunity.

“This is my dream job,” she describes excitedly. “Coral reefs are amazingly diverse ecosystems that are beautiful, complex, and full of interactions with the many species that live within them, and they also provide so many benefits to humans. Coral reefs fill me with so many scientific questions and opportunities to study and understand how we are negatively affecting them—and, most importantly, what we can do to protect them.”