Over the past three years, CORAL has been privileged to work with world-class researchers from academic institutions and conservation organizations as part of the Reefs Tomorrow Initiative (RTI). Launched in 2012 with a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, RTI’s goal was to understand how multiple factors—for example, wave energy, herbivores, and the distribution of coral species on a reef—interact to affect the health of a coral reef. In conjunction with our scientific research, we worked with coral reef managers around the world to understand how they use science to inform their management decisions.

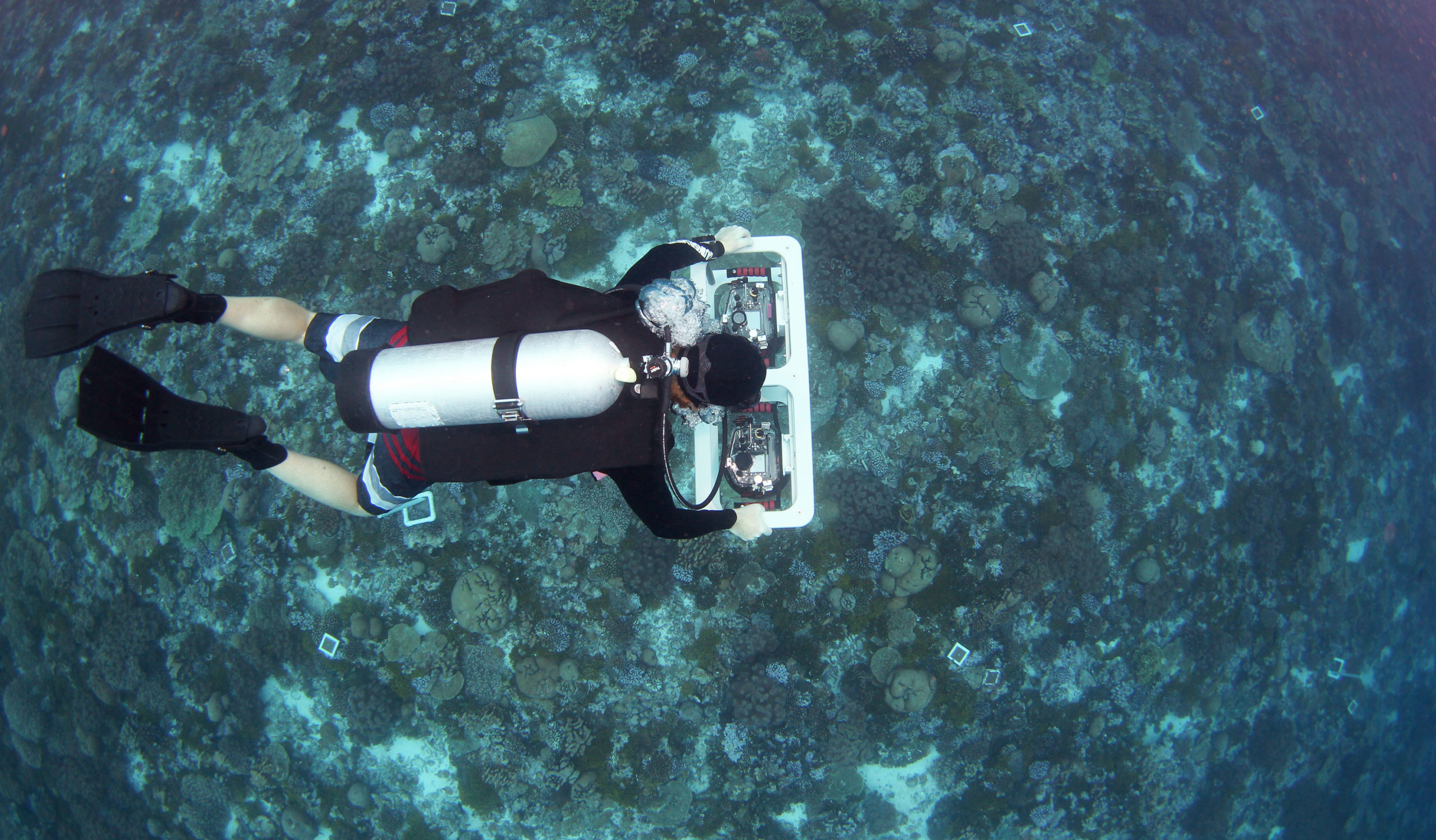

We based our scientific research on the remote atoll of Palmyra in the central Pacific. Armed with cameras, clipboards, settlement tiles, temperature data loggers and more, we collected a truly staggering amount of biological, physical, and ecological data. Simultaneously, we worked with communities around the world—including partners in Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Palau—to make sure that our scientific work was relevant to conservation and management challenges.

Now that we have completed RTI, I wanted to share some of our key findings:

- In areas not impacted by humans, there are rules that dictate how reef-building corals are distributed on a reef—that is, there’s a certain amount of determinism to who lives where. In more degraded systems, these rules tend to break down. Using mathematical models and data from Palmyra, we are exploring what this means for reef resilience and management.

- The resilience of ecosystems cannot be decoupled from the resilience of human communities. For example, for communities to be resilient to storms, their ecosystems must be resilient as well. Knowing this, we have been able to improve the way we share scientific information with natural resource managers.

- Not all herbivores are created equal. Through RTI’s work, we are learning that the effects that herbivores can have on a reef depend on their behavior, size, home ranges, and where they feed. This information will help us better manage herbivores on reefs.

- Coral reefs protect shorelines by absorbing wave energy. Through work at Palmyra, we discovered that healthy reefs can dissipate significantly more wave energy than more degraded reefs. This suggests there may be a feedback loop whereby degradation of a reef’s physical complexity results in the reef experiencing greater wave energy, which in turns leads to further degradation of the reef.

We have combined these and other findings into a mathematical model that allows us to explore how climate change might affect reef health by increasing the frequency and intensity of disturbance events. If we know how healthy reefs, like those at Palmyra, can withstand change and recover from disturbance, we may be able to unlock the key to this resilience for other reefs around the globe.

While funding for RTI has ended, our collaborative work will continue for years to come as we build on what we have learned from Palmyra and our work with communities around the world.

Members of RTI include American Museum of Natural History, Coral Reef Alliance, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Stanford University, University of California – Santa Barbara, University of North Carolina – Wilmington, Victoria University of Wellington. More at www.reefstomorrowinitiative.org.